Product Strategy for Machine Learning

Specifically written for product managers, this article is designed to give a useful framework for thinking about machine learning and artificial intelligence.

It isn’t obvious that adding to the plethora of existing material on machine learning is worth the readers or the writers time. The focus of this piece is the product strategist, meaning: he team or individual tasked with allocating within or among products to drive market share, revenue, profitability, growth, or whatever feeds the companies strategy.

It is divided into three parts. First, a closer look at what machine learning or AI really does - namely what a prediction is. Secondly, we consider the options for implementing machine learning in light versions, such as prioritizing which sales lead should be contacted first to full-on implementations such as self driving cars. Third and lastly we take a look at the key aspects of data.

What does machine learning do? A closer look at what a predictions is.

A deceptively simple answer to the question what machine learning does is: “it improves prediction making”. This, of course, is meaningless unless we understand “improving” and “prediction”.

What is a Prediction

Predicting over time

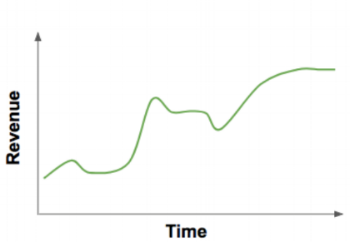

The word prediction can be a bit tricky because of the way it is usually used. A typical prediction that a product managers comes across would be revenue over time.

A “revenue forecast” is nothing but a prediction over time. Revenue could also be predicted among other dimensions, say by product, in any case both are just predictions.

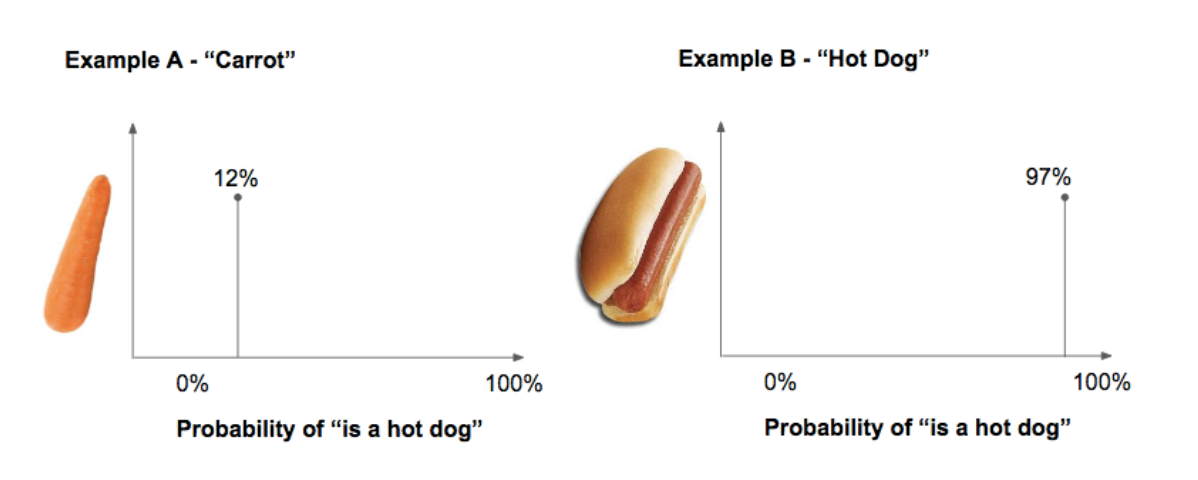

Now, let’s change what is at the axis. Let’s say we are predicting whether or not something is a hot dog or is not a hot dog.

The input for this specific prediction is a picture.

If we look at the X axis, we see that the unit is the probability of the object “is a hot dog”.

Of course, for a human it is easy to differentiate between pictures because humans just happen to be very good at getting and interpreting visual data. In other words, we can see things and know what they are.

But, if you (or any other human) were asked to make the same prediction to give me this information:

It would be much harder for us to predict which of the lines here represent a hot dog. That is just to say, different data can be used to predict the same thing, the probability of whether something “is a hot dog”. Now, back to the picture example.

“Improving” decision making

As a human, when looking at the picture of a carrot and a hot dog, we just recognize which one is which.

But, if I wanted to try to write a program that predicts whether something is a hot dog we might approach it like this: First define a range of typical colours of a frankfurter. Second we define a range of typical colours of bread. Then we define, whenever the ratio of “frankfurter pixels” divided by “bread pixels” is 45% - 75% then the probability that this is a hot dog is 100%.

Now, it is probably obvious that this is highly impractical given the varieties of pictures with hot dogs. Plus, it requires knowledge and an decision-making of how the different factors weigh in.

Machine Learning uses a different approach: after providing a set of correct predictions, pictures labeled as hot dogs (called training data), the computer considers all the factors it finds and weighs them by which factors are most useful in predicting which object is a hot dog and which one is not. This has three consequences:

First, much more and much more complex factors can be processed by a computer than by a human.

Second, we do not know (or more correctly, it is very difficult to re-trace) what the algorithm uses to make it’s prediction. The algorithm might have used our “bread pixels” to “frankfurter pixels” or it might not.

Third, it can be much faster and much cheaper to build a good prediction machine compared to a human. This however depends on the prediction in question and the available data.

How to make a feature out of machine learning? Basic options for implementation.

Machine Learning is about making a prediction. Yet, a prediction has zero value without action resulting from that prediction. How the prediction is taken into action is a separate step. There are different ways of segmenting or thinking about the action part.

Option 1: Offer suggestion to the human

For example, let’s look at CRM system. A CRM is basically a list of potential customers. It is key decision whom the sales representative calls first. A sales representative might only get to make 10 calls per day, so who get these calls matters greatly. Now, let’s say we have trained our prediction machine so it reliably outputs which customer is most likely to buy.

The CRM system might offer the sales representative “10 suggestions” of whom to call each day. These suggestions are simply the predictions of the lead that have the highest likelihood to buy.

Yet the point is, the human still take it’s own decision and can therefore use information that is not captured in the CRM. Say, the sales representative had just been at a conference where he met a potential customer that was very eager to buy. So the sales representative might overrule the machine.

Option 2: Define the workflow

For the second option, let’s assume we have build a workout app. Our goal is to make sure that our users finish the 90 day fitness course. Of course, we want to push our users so that they see results of their workouts. But, we also know that there is a risk of users ending the app use altogether.

Let’s say, we can build a prediction machine on how likely our user is to stop using the app. Data included could for example be how long the user takes per exercise, at what time of the day the workouts happen or a form of user feedback such a question “how exhausted are you on a scale from 1-10”.

Based on the prediction we could than moderate the fitness program for the next day. We could make the app include less of the hardest exercises and instead add some more enjoyable elements. In other words, the human still takes the action but has, in comparison to the first case, no choice in the matter.

Option 3: Let the computer take action

In the most extreme case both the prediction and the action are handled by a machine without a human interfering. The obvious example is a self driving car - it combines prediction and execution. In such an autonomous car there are massive amounts of predictions happening simultaneously - “is the road going left or right?”, “is the child walking on the sidewalk or is it running onto the street?” with relatively few outputs, acceleration, braking and steering, also taken by the machine.

While this is a well known scenario, It’s useful to look at a simpler case. Let’s say we have build a prediction machine for football betting. Following a prediction the machine can bet. Yet, that is not the end: how much can the machine bet? How certain must the probability be to bet how much? Who, at the end, is responsible for the money that could be lost.

In this example the context is only money - these questions which include responsibility get more tricky in other context. Medical diagnoses or the above mentioned autonomous car. Going deeper into these questions far exceeds this piece.

However, allow me one comment - when comparing different solutions it might be useful to be clear about what the ultimate objective if. Or, to be drastic, what is better: 3,500 annual deaths from cars driven by humans or 200 annual deaths from car driven by machines? Note, that I am not arguing that the number of deaths is even the ultimate objective, maybe it is human agency or something else. Clarity about what is being predicted and who takes action is necessary to discuss these questions productively.

How to fuel the machine? Considerations for dataset valuation

When somebody is “doing machine learning” they are not defining how a machine learns but they are teaching a machine that already knows how to learn. That is, because actually enabling machines to learn is a both highly abstract (really difficult) and is software and thereby has virtually zero marginal costs.

Or, take the business perspective: you will not be able to build machine learning algorithms because the talent is extremely rare. And even if you were, you would will not be able to make money because you don’t have the scale to sell them.

Thankfully, machine learning algorithms are widely available in different formats from free libraries to hosted cloud platforms that combine providing, running and storing the algorithm - AWS, Google, Azure and others.

What most “doing machine learning” usually means is gathering, preparing and using data such that you are able to a) generate predictions that are better than the current alternative and b) have ways to let the appropriate action by executed which reduces costs or risk or, even better increases revenue.

There are two sets of data that are vital to the success of this operation. Success means that your prediction is better than what’s currently being done and that the quality of the prediction continues to improve.

Training data - This contains the data you want the prediction machine to use, plus the correct result. For example, if we were to train our hot dog vs. carott prediction machine we might generate source hundreds of pictures and crowdsource the labelling. Mechanical turk is a common tool for this. In the case of picture labelling this is of course quite straight forward because most people know what a hot dog is. That is different for other training - if you think back to the case of the CRM system you would need to have a number of leads with their characteristics plus whether they have bought something in a given time frame or not. That might be difficult data to get.

Feedback data - The second component is feedback data. Not only do you want to train your prediction machine but you want to prevent it from getting worse. This means you need to capture the results of the action which were based on your prediction. Think back to the Fitness App - did the action taken by the app really reduce the likelihood of a user stopping its usage? To judge this you need to know whether a user actually stopped. Or, in other words, you do not want the outcome to “leak”.

The big picture on product strategy for machine learning

Besides the buzz and the speed at which machine learning topics move, the process for the or product strategist can be broken down into a relatively simple questions to ask yourself in the given case:

What is the exact outcome I am predicing?

What is the gained value of the right prediction and what is the lost value of the right prediction?

How will the prediction be translated into action?

With the dataset I have right now, can I predict noticeably better than whatever is doing the prediction today?

What is my path to even better predictions? How will the feedback from actions be incorporated?

If you do not have clear answers to the questions 1-3 you need to get back to basic product management - understand workflows and understand the economics of you user by talking to your users. The machine learning canvas is a good tool to do that. I

f the answer to question 4) is “no”, than you have a data problem. Question 5) should get you thinking about the future of your product on a more strategic level.

Recommended Resources

Hopefully this article gives you an overview to ask good questions to dive deeper, for example "how exactly mathematically does this work?", what is the difference between "machine learning and artificial intelligence"? Without having that question it is difficult to read well. Anyway, below is a set of pieces I want to give respect to for they have helped me.

https://medium.com/machine-learning-for-humans

http://investorfieldguide.com/ash/

https://www.amazon.com/Prediction-Machines-Economics-Artificial-Intelligence/dp/1633695670

https://medium.com/louis-dorard/from-data-to-ai-with-the-machine-learning-canvas-part-i-d171b867b047

https://a16z.com/2017/03/17/machine-learning-startups-data-saas/

Reading

In this article I put out my opinion on the comment complain “i don’t find enough time to read” and how to think about reading in general.

The Warren Buffet Diet

One of the things that annoy me in conversations, medium, blog and twitter posts are things like “This year I read 12 books”, “goal for 2018: read two books per a month” or “read like warren buffet - the 500 page diet” . In conversations this topic of wanting to read more, or not having time to read, or having so many books not yet read comes up quite a lot as well. I am not sure why this annoys me so much. Partly, I think it is because of the status connotated with reading books and hence the benefit of claiming to read a lot or wanting to read more.

Here is how reading (books) breaks down for me. Obviously, that is specific to everybody's lifestyle.

Basic time mechanics of reading

The average time to read one page is 2 minutes. The average book contains 300 pages. That means the average book takes 600 minutes or 10 hours.

To be useful, numbers have to broken down on a daily basis to grasp them. 600 minutes means 20 min per day. If you smoke, that’s about 6 cigarettes. If you commute to work by train your time use probably looks like 2 x 20 min per day for 20 working days which is 800 minutes or 133% of a book a month.

Now, I travel at least once per month. Travel usually means 30 minutes to the airport, 30 minutes in security, 30 minutes at the gate. 60 minutes on the plane. That’s 140 minutes on way, or 280 minutes both ways. Or 46% of a book a month.

In other words - I and most people certainly have the time to a book a month. Adding to this, if you commute by car audiobooks also do about a 2 pages per minute. I for example also listen to audiobooks while running. If you want to make sure you read 20 min a day you could just get a daily tracking app like daylio (google it) and check it of.

Breaking down “I don’t have enough time to read”

When you say “i don’t have enough time to read”, there are two components to this statement.

Component 1: The expectation of number of books you want to read.

Component 2: The time you spend on reading.

Reading a book a month is a decent reasonable expectation. But also is 2 books a month, or 0 books a month. There is no morality or worth attached to reading or not reading. If you do not read a book a month, then the problems could be:

1) You do not have the time

2) The book you are reading is not interesting

3) You don’t really like reading

You do not have the time - not true.

I think this is generally not true. In the combination of reading in the morning, reading in the evening, during a commute, listening to an audiobook while running or cooking.

You don’t really like reading - often true

In the previous point we saw that you do have the time to read. Given this, if you still do not read and also have a good book to read, you are not actually interested in reading. Don’t claim you don’t have the time to read. You are lying to yourself. Admit you don’t like to read and get on with something you do like.

The book you are currently reading is bad - often true

When ever I read less than usual this is the cause. The majority of books in the world are not interesting to me.

The writing could be bad or the content is less interesting than I thought when I bought the book. An example of the latter are the books “Astrophysics for people in a hurry”, “Asking Essential Questions”, “The Gulag Archipelo”, “The Genius in the System” and a number of books that I don’t remember because I gave them away.

Recapping this section: you have the time to read. You either like to read or you don‘t like to read. Most likely you don’t like the book you are currently reading but you are still reading it.

If you start reading a book, chances a higher you don’t like it then that you do like it.

That is true because you know nothing about the book before your start reading it. Unless you read books by an author you know. You might know about something like “Steffen recommended it to me” or “It is about a topic I am interested in”. Once you read about 10-20% you actually know if the topic is interesting or if it is well written. I’d say it is safe to assume that you don’t like about 50-70% of the books you start.

For some reason there is a shame associated with not finishing a book. I’d not know why that is, but I do know that it is stupid. You buy a book with close to zero information that will determine whether you like it or not. If you find out that you do not like it, it is somehow bad to not finish the book.

That is really dumb because:

1) You will read less books in your life because you read slower and less often when you do not like a book

2) You will spend more time of your life reading books that you don’t enjoy.

Because it is more likely that you like a book as opposed to you not liking a book (see above), by arguing that you “need to finish a book” you are making an active decision to have a worse life and learn less.

Also, storing books is stupid, but that is another topic

Search Funds / Unternehmensnachfolge / Konferenz

Ich habe in den vergangenen Monaten relativ wenig geschrieben, das liegt daran, dass ich mit Ookam gut beschäftigt bin und auch dort regelmäßig schreibe.

Es gibt wenige gute Erklärungen, daher hoffe ich das der Artikel einen Überlick gibt und gleichzeitig die relevanten Quellen für eine weitere Beschäftigung mit dem Thema enthält.

In diesem Zusammenhang ist auch die https://www.nachfolgeunternehmer.org/ erwähnenswert. Eine Konferenz die wir am 5. Juli in Berlin veranstalten. Für einen discount code, einfach eine Mail an: s.buenau@gmail.com

Brauche ich eine UG oder GmbH, was ist ein Gewerbe und was ist die Kleinunternehmerregelung?

Aus eigenen Fehlern gelernt eine kurze Zusammenfassung zum Thema Freiberufler vs. Gewerbe oder GmbH. Persönliche Sicht.

Kurz Zusammengefasst meine Erfahrungen zum diesem Thema. Damit andere die Fehler, die ich gemacht habe, vermeiden können. Es gibt natürlich noch Aspekte die über das hier genannte hinausgehen, Fokus ist hier die Beantwortung der Problemstellung.

Problemstellung: Ich möchte ein paar Beratungsprojekte machen und muss dafür Rechnungen schreiben. Was jetzt?

Frage 1: Brauche ich eine UG oder eine Gmbh?

Eine GmbH ist eine Kapitalgesellschaft. Der gesamte Sinn dieser Struktur ist die Vergemeinschaftlichung von Risiken und die Aufteilung von Profiten. Deshalb gibt es diese Gesellschaftsform. Beispiel: riskantes Projekt Eisenbauprojekt geht schief. Trägt die Risiken und Gesellschafter gehen nicht in die Privatinsolvenz sondern das Kapital in der Kapitalgesellschaft trägt das Risiko

Zweiter Aspekt: steuerlich relevant wird Geld das aus der Kapitalgesellschaft ausgeschüttet wird. Re-investiert man das Geld innerhalb der Gesellschaft fallen keine Steuren an.

Hinweis: eine UG ist das gleiche wie eine GmbH, es muss am Anfang nur weniger Geld eingezahlt werden, in anderen Worten: weniger Kapital ist notwendig (1 Euro vs. 25,000).

Wenn man keine Risiken und keine Re-Investitionsmöglichkeiten innerhalb einer Rechtspersönlichkeit hat, führt eine Kapitalgesellschaft zu hoher Komplexität (2 Tage Einrichtung, 2-3 Tage prio Jahre maintenance), einmaligen Kosten (Notar, Kontoeröffnung), wiederkehrenden Kosten (jährliche Bilanzpflichten, Geschäftskonto) und Schriftverkehr.

Wenn man einfach ein paar Beratungsprojekte für 10,000 Euro im Jahre nebenbei machen will braucht man definitiv keine GmbH oder UG. Außer man hat Bock auf laufende Kosten von 500 Euro pro Jahr und nochmal 2-3 Tage Aufwand und Nerven um die Sachen zu managen.

Frage: Bin ich ein Gewerbe?

Es gibt eine Liste von Berufen, die eine Gewerbe sind. Diese Liste findet sich hier. Wenn man “Beratung” macht dann ist man nicht auf dieser Liste und deshalb ist man kein Gewerbe.

Frage: Alles klar, was bin ich jetzt und was muss ich machen?

Kapitalgesellschaft macht keinen Sinn. Gewerbe ist man nicht weil man nicht auf der Liste steht. Deshalb ist man Freiberufler.

Damit man damit eine Rechnung schreiben kann, googlet man “Freiberufler” und den Namen des Finanzamtes bei dem man gemeldet ist. Da muss man eine Anmeldung ausfüllen und bekommt eine Steuernummer für Freiberufler. Kostet nichts/wenig. Dann hat man eine Steuernummer.

Jetzt kann man Rechnungen schreiben, denn die Steuernummer ist Bestandteil von Rechnungen. Auf einer Rechnung muss eine Steuernummer stehen, damit der Staat nachvollziehen kann wohin das Geld fließt.

Damit ist man im Grunde fertig - bei der Steuererklärung gibt man das Einkommen - Kosten als Gewinn an und damit ist die Sache fertig.

Frage: Was ist mit der Umsatzsteuer oder Kleinunternehmerregel?

Das Problem bei der Umsatzsteuer ist, dass der Staat die Umsatzsteuer haben will bevor Sie anfällt. Die Umsatzsteuer ist 19%, bedeutet wenn meine Vorhersage ist, dass ich im nächsten Jahr 100,000 Umsatz mache, dann muss ich in diesem Jahr 19,000 vorausbezahlen. Wenn ich dann weniger Umsatz mache, bekomme ich die entsprechende Differenz zurück. Offensichtlich muss ich aber erstmal die 19,000 Vorfinanzieren.

Dieses Problem ist gelöst mit der Kleinunternehmer Regelung. Umsatzsteuer fehlt nicht an wenn der Umsatz “im vorangegangenen Kalenderjahr 17.500 Euro” und “im laufenden Kalenderjahr voraussichtlich 50.000 Euro” betragen. Man möchte unter diesen Regelungen bleiben, weil man sonst das ganze Zeug an der Backe hat. Auf der Rechnung muss der entsprechende Paragraph für die Kleinunternehmer Regelung genannt werden.

Was ansonsten auf eine Rechnung muss lässt sich ergooglen, plus siehe den zweiten Teil.

Frage: Brauche ich ein Spezialkonto?

Nein. Ist nicht notwendig (im Unterschied zur Kapitalgesellschaft wo man in der Tat ein Geschäftskonto führen muss was Geld kostet). Aber, es kann sinvoll sein und zwar aus zwei Gründen:

a) werden die Einnahmen sauber getrennt

b) manche Konten enthalten Rechnungsstelltools so das man nicht per Word Sachen erstellen muss

c) mache Konten enthalten Tools um Kosten die gegen Umsätze getracked werden können.

Persönlich nutze ich für die Features a) und b) Holvi. Generell ist es organisatorisch sinnvoll die Einnahmen direkt zu trennen weil man dann schlicht bei der Steuererklärung weniger Zeit braucht.

Frage: Was kann ich steuerlich absetzen?

Besteuert wird der Gewinn. Gewinn ist Umsatz - Kosten. Die Frage ist dementsprechend welche Kosten. Das ist ziemlich nah am Common Sense, nein ein Anzug ist keine Ausgabe auch wenn man ihn im Job trägt, eine Zeitungsabo auch nicht. Ein Laptop potentiell teilweise und direkt Zusammenhängende Kosten auch. im Zweifelsfall Steuerberater fragen, Googlen oder ausprobieren.

Next actions:

Finanzamt anrufen und nummer beantragen

Kunden happy machen und Rechnungen schreiben

Wenn die Rechnungen zu nervig werden ein passendes Tool suchen.

Pricing and Discounting - Introduction for Product Managers

Pricing is extremely important but has many 2nd and 3rd order effects that were not obvious to me. Summarising what I learned about pricing and unit economics from a product management perspective in this post.

It appears that price reductions and discounts are often done without a clear understanding of the goal. Of course, as consumers we see discounts nearly every day from clothing, to plane tickets and other products. But, this does not explain if and when discounts makes sense and when they don’t.

In this post, I am will go through an example both of potential goals as well as do the math on whether a price discounts is the right tool to approach that goal.

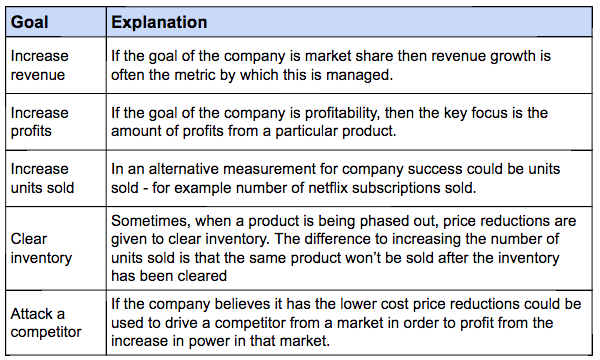

From a strategic perspective there are 5 potential goals:

Strategic reasons to drop a product price temporarily

This is a football net.

To make these clearer we will be working with an example. I'll be using a company that sells footballs. I think everybody know what those are.

Also, football nets will play a role. Football nets are those things you can carry balls in. See picture.

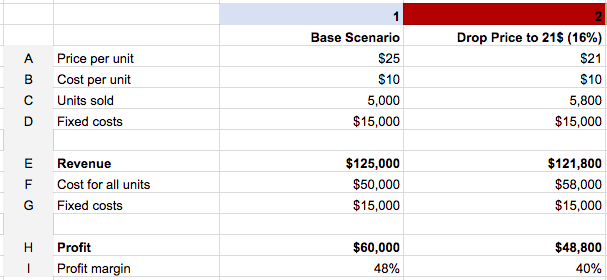

If you are interested in the excel from which I am taking screenshots, you find that here.

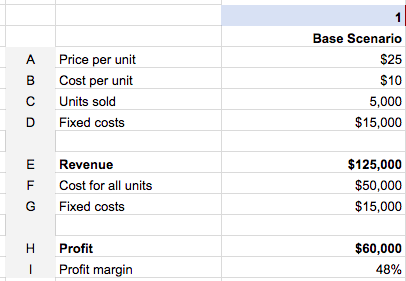

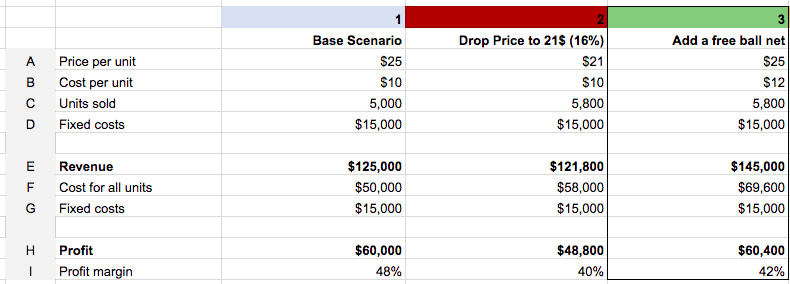

Example Set-Up

Price per unit: The price a customer pays for one ball

Cost per unit: The cost of making the ball, shipping it to the customer, with packaging, shipping and everything else associated with one ball.

Units sold: Number of units sold

Fixed costs: Costs associated not with selling one ball but with the business in general, like the rent of the office or the tax advisors. This does not change with the number of footballs sold.

Revenue: That is simply (price per unit) x (units sold). In this case: 25$ x 5,000

Costs for all units: (costs per unit) x (units sold). In this case: 10$ x 5,000

Fixed costs: Explained above, so in this case $15,000

Profit: Revenue - fixed costs - costs for all units. So in this case: 125,000$ - 50,000$ - 15,000$

Profit margin: (profit)/(revenue). So in this case: $60,000 / 125,000 = 48%

Goal 1: Reduce prices to increase revenue

The question is this: if we decrease the price by 16% and our demand increases by 16% does our revenue increase? (Yes potentially there could be an increase in demand higher than 16% - check out the excel to model that yourself). Let's look at the numbers.

First, we drop the price from 25 or 21 USD, that is line A. This is a 16% drop (4/25 = 0.16). Now, let’s increase the demand by 16%. Our new number of units sold is 5,000 x 1.16 = 5,800 units, which you find in line C.

This just means: our price dropped by 16%. Our volume increased by 16%. What are the effects:

Revenue: decreased from $125,000 to $121,000. We have not achieved our goal of increasing revenue because revenue has dropped.

In addition, we have eliminated $60,000 - $48,800 = $11,200 in profits. That is also not good but does not concern us strategically because we want to grow revenue and not profits.

First conclusion: if we drop price by 16% and demand increase by 16% we don't achieve our goal of increasing revenue and we also loose profits. You can do the math based on the excel linked above, in short - you would need an increase of demand by 20% in exchange for a drop in price by 16% to increase your revenues.

Goal 1 - Increase revenue. Additional considerations.

Besides the simple numbers we have just done, there are other consideration when looking at decreasing price to increase revenue. Let’s go through a couple of them.

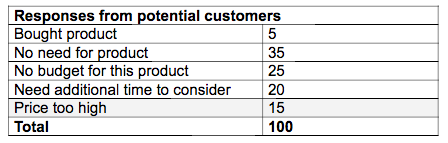

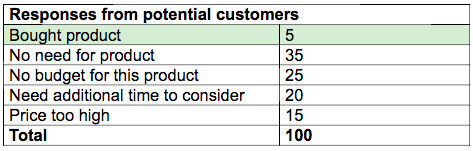

Price discounts only work for customers you lose because of the price

If you make 100 sales pitches per month, have 100 people visit your website or have 100 people come into your store - a price discount does not increase this number per se. If only affects the sales pitches you make and which you lose on price.

Simplified win/loss analysis results to understand what pricing drives

If this is the split of the results of your 100 pitches, you can only expect an effect on those 15 pitches that are lost on price. That is the number marked grey in this table.

Without massive advertisement (which has a cost) you will not increase your revenue through a decrease in price. In other words: if you do not reach your customer, a price of 0 does not change the number of customers you reach.

Combining this with the above: the 16% increase in units sold we assumed above does not just happen. It still needs advertisement. Most important customer need to know what the price is in order to buy because of a lower price.

Alternative: spend the money to generate more leads

If we need to spend money to broadcast our message of lower prices. We could also spend the money on increasing without lowering the prices. In other words – increase the number marked yellow.

Why not spend the money you spend anyway without dropping the price?

Alternative: spend the number on training/improving sales

Another alternative use of the cash you will spend on telling people that you dropped prices is to spend it on the conversion rate. You could spend the money on inviting all your existing customers to lunch to understand why they bought. You could hire a store assistant or spend the money on training your sales team or update their tools and systems. Or you spend the money on new packaging so that the potential customers you do have understand the benefits and are persuaded to buy.

In other words, change the number in green by improving your sales game.

What if price is not actually the reason why you loose business?

In short: first understand the reason why customers are not buying. If that is the price, there a discount might help. If it is not the price, a discount won’t help and you might end up only loosing money.

Goal 1: Give something for free instead of decreasing the price

An alternative to dropping the price is adding something for free. For example, if you are selling footballs you might add a free ball net.

For example, The Economist is currently adding a free USB stick. Certainly not because the average Economist reader does not have the money for a USB stick.

What about something for free instead of a cheaper price?

But why is this a good alternative? There are obvious strategic reasons – you do not train your customers to expect discounts. You can add variety to your campaigns by adding different stuff but discounts are just discounts. As an idea, you could add an hour of “free consulting” from your CEO/Product Manager/Head of Sales and so actually learn more from your customers.

Of course, this “soft stuff” is not enough. Let’s look at the example numbers. Our goal is still the same: to increase revenue.

What happens when you give something for free?

Our price stays the same, $25 (Line A). Our costs increase by $2 because we have to buy the ball net (Line B). We assume that our units sold go up by 16% because our customers really like the ball net. That assumption is basically on the same level as assuming demand increases by 16% if you drop the price by 16% - both need to be tested. Let’s look at the effect:

Revenue: revenue is up. We have achieved our primary goal!

Profits: Increased by $400 as well. Our profit margin is a bit lower but since we are looking for market share, not profitability that is alright.

This alternative of giving something for free seems to be much more appealing than dropping the price! Of course, it hinges on the % increase of orders but it is not obvious that people like free stuff less compared to reduced price.

Goal 1 - Summary

First, understand why customers are not buying. Second, consider adding a free gift but keeping the price.

Goal 2 – Increase units sold

Now, our goal is to increase the number of units sold. This is only different from revenue because sometimes this is a better reflection of the stage of your company.

For example, for Uber the number of signed up drivers might be the key metric because it is an indicator of market power. Similarly, netflix regularly reports the number of subscribers as a key metric. The assumption probably is that once you have the customer subscribed you will turn a profit at some point.

In these scenarios a table like the above makes less sense because you have to take into account the available capital. Business like Uber and Netflix are able to raise the money to finance the growth even at a per unit loss because the monetisation is assumed to be possible

A meaningful way to think about this is not the revenue calculations we did above but understand the reasons why customers are not buying.

If we look at the same table as before, we see a 5 people actually buy the product out of 100 we pitched.

Why uber and netflix don't care about prices

So, in a business where the potential base is extremely large (like becoming an Uber driver or subscribing to Netflix) you likely focus on the other reasons why customers are not buying.

Your whole focus is the customer acquisition and the price is only a small part of this. A bigger problem is getting everybody to know about Netflix rather than lowering the price. That’s probably why Netflix initially did not care about customers using the accounts of their friends. In general the problem is not the price of netflix, especially when customers get older, but that everybody needs to know about it.

Unfortunately, your market is probably to small to justify this strategy.

Goal 3 – Clear inventory

A case in which price discounts do often make sense is clearing inventory. Inventory can be seats on a plane that flies anyway, empty hotel rooms at the end of a day or clothing from the previous season. While the cost of clothing obviously does not go to Zero, it is looked at in comparison to the new season stuff. At the end of the Winter season, it is cheaper for H&M to drop the price drastically for customers to buy it rather than the alternative. The alternative would be to throw away the stuff to clear the retail space for new season stuff which does have a higher price.

The difference to the example given at the beginning is that the “marginal costs” are close to 0.

The equivalent would be where the next football does not cost $10 but maybe $0.5. That would mean you are turning a profit whenever you sell higher than $0.5. Typical examples:

plane seats (the plane is flying anyway)

hotel rooms (hotel is built and rooms are equipped)

clothing from last seasons (the space needs to be freed up to for the next seasons)

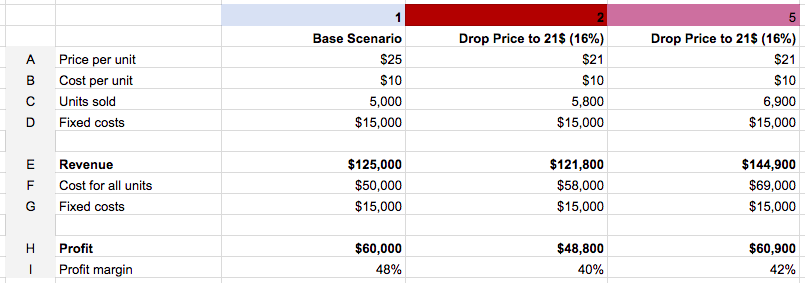

Goal 4 – Increase Profits

As we have seen above it is quite difficult to increase revenue through price reductions. Increasing profits is even harder because profits are: (price) x (units sold) – (units sold) x (cost per unit) – fixed costs = profits.

If you are dropping price you first need to sell more to get to the same revenue. Next, because the difference between price and costs per unit has been decreased you need to sell an extra amount more to increase your profits.

What you need to increase profits through reduced prices

Blue (Column 1) is our base scenario. Red (Column 2) is what we looked at before. Violet (Column 5) is what we look at now.

The question is: if we drop the price by 16% (row A) by how much does the demand need to increase in order for profits (row H).

I have played around with the demand figure until I got the profits above $60,000.

The answer is: for a discount of 16% sales need to grow by 38% for the profits to increase. That is massive increase in demand, possible but unlikely.

I would claim that unless your whole reason of being is to cut costs, like Ryanair or Aldi it is extremely difficult to grow your profits through cost leadership.

Goal 5 - Attack a competitor

Included for the sake of completeness - I don’t know much about this so I will not comment deeply.

Only one thought: if you drop prices - the opponent either follows this move or does not follow.

If the opponent follows by also by reducing pricing, you want to make sure that they leave the market. Because if not, you might just end up with the same market at lower prices. That would the worst outcome.

Now, if your competitor does not follow but stays in the market with a higher price point and you don’t win over customer from the competitor you know that the problem is not the price. It is the product.

Summary

Unless you are clearing inventory, price reductions rarely work. Re-visit the goal you want to achieve and consider the alternatives.

German Software Stocks - Financial Analysis Intro

As stated previously I will analyse German Software companies. Most financial information is meaningless to me for the purpose of arriving at an attractive price. I can of course compile benchmarks and understand why current coverage, cash cycle theoretically matter but I don’t feel comfortable with it.

What I will do instead is put a value on the whole business then divide that by the number of shares. That will give me the price that I’d be willing to pay for more shares.

But, before I do this I want to share my approach so that I do the same thing for all companies and can improve. This is also written fast and based on common sense. I write we because I own a share of each company.

I will keep this part purely financial, some of the questions serve as preparation for qualitative research or asking the management.

Questions I want answers to:

- Does selling the current products make more cash than it costs to make them?

- Are there more customers for the products with similar acquisition costs in the future?

- Have less people bought our products in the lastly?

- Are we making a lot of investments?

- Have we made a lot of investments in the past?

- How good have the past investments been?

Definition of “Investment” and “Investment” in the context of Software businesses

An “investment” is something that you do today to generate cash in the future. If it does not generate cash it was a bad investment. But, if it does generate cash it is not automatically a good investment. Because it could also not be an investment at all.

Example: If I am in the business of selling balloons on the Oktoberfest, than the thing to put gas into the balloon is not an investment. Yes, it generates cash. Yes, it is re-used when there is gas filled it. But if I buy a new one, I cannot tell my investors that I have “invested” in something. The new gas thing will not generate more revenue at the next Octoberfest, it will just allow me to do any revenue.

Normally, I would expect to find the “investments” in the assets on the balance sheet. Now, in case of software, most likely there will not be an asset on the balance sheet but I expect it to be somewhere on the incoming statement - hidden as labour costs.

Enough theory, let’s start

I feel there has been too much theory from me. I will start and later come back to this article. The questions above still stand.

Book review: The Stuitcase by Sergey Dovlatov

Very brief note on the book “The Suitcase” or “Der Koffer” by Dovlatov which I have just finished. In a sentence: recommend!

I will fall out of my regular checklist for book reviews. I have just finished The Suitcase by Dovlatov while on holiday. Very entertaining and easy to read - joyous book. Not sure how true that is without having spend time in Russia but I think it is still fine and a good read.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sergei_Dovlatov

Book review: Charlie Munger: The Complete Investor

This is the review of the book “Charlie Munger: The Complete Investor” by Tren Griffin. Tren Griffin is one of my favourite bloggers and one of the few blogs I go visit to check if he has written something new. First review of a book consumed via audible.

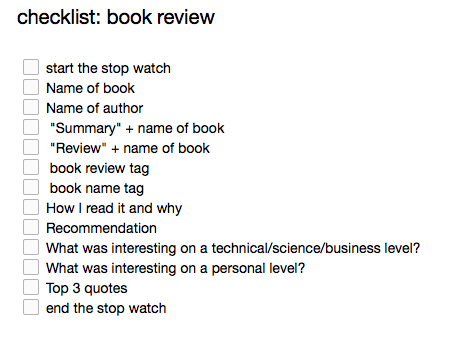

I am trying to find my tone with these books reviews, so they vary in style and size. One of the things that I have started is to write a "book review checklist", inspired by the "Checklist Manifesto" to make it easier and faster for me to have decent quality consistently.

My checklist looks like what you see on the left side. If you are wondering why I include summary: Charlie Munger: The Complete Investor by Tren Griffin than that is quite simple: basic SEO.

I have been inspired to write content here a bit more regularly by a recent interview of Benedict Evans with Bloomberg Radio "Masters in Business Podcast". Here he describes two things. First on how he got a name in blogging:

"(...) I sort of got noticed and you know I spent like two or three years writing about posts and getting like 100 page views a month and then I went through a period where I was getting a couple of thousand page views a day and that sort of happened in the course of 2013."

We are a bit of over focussed on relatively short term outcomes, but more complex elements take time. There is very little magic to that. Also, there is very little magic to how Bendict Evans got the job.

"EVANS: I just asked them for a job. I don’t know why people said it is hard to get a job in (INAUDIBLE), you just ask them for a job, they say yes."

Anyway, back to the book review. How did I read it and why: basically, I am very big fan of the content by Tren Griffin, for example https://25iq.com/2018/04/07/business-lessons-from-mark-leonard-constellation-software/. I have gotten more and more interested in Charlie Munger following the Biographie of Buffet (review of the The Snowball

I listend Tren Griffins book on audible. That makes it difficult to write a summary because I rely heavily on the notes and highlights I can take on kindle.

Recommendation:

Highly recommended if interested in "mental models" and value investing specifically. Without an interest in this, it is not going to be interesting. If you listen to/read farnam street stuff or tim ferris podcasts than this is probably interesting. If not, than buy it cheaply (audible free book) and try if you like it.

Also read:

https://25iq.com/2016/11/25/a-dozen-things-warren-buffett-and-charlie-munger-learned-from-sees-candies/

https://25iq.com/2015/10/30/a-dozen-things-ive-learned-from-charlie-munger-distilled-to-less-than-500-words/

What was interesting on a technical/science/business level?

- The biggest lesson is that it is easier to avoid stupidity than achieve brilliance. If done over a long period of time this compounds and leads to great value.

- What is risk: this I find very interesting because I remember asking my brother this about 10 years ago when I finished school and he was working in the quantitive section of a large bank. I have never found a useful definition of risk (volatility makes not sense for me because volatility measures volatility not risk - otherwise it would be called risk).

What was interesting on a personal level?

Nothing to comment here in particular here, a very business focussed book.

Top 3 quotes

Not available because I consumed this on audible.

Time taken to write this post

30 minutes.