Can “easy way” be applied to other stuff?

A lot of actions that improve life a lot - doing 20 push ups a day, flossing teeth, sending thank you letters to friends, calling people take very little time and effort but are not happening.

So, somehow they must take more “effort” than we think. On interesting case

Allen Carr’s “Easy Way” is interesting, since a) works for me, b) is cost and time effective and c) works with the patients mind in understanding the consequences of behaviour and does not outsource things to a higher authority or alike.

How the Easy Way works

Clarifying the largest part of the addiction is mental, not physical

Replacing the perception that it is difficult to quit by the mental pattern hat keeping smoking is more difficult than not smoking. Apart from the addiction, which as per (1) as been clarified to be mostly mental.

That's already it

Probably this is not very intuitive to non-smokers. But the benefits of smoking are also not very intuitive for non-smokers - which is the frame of mind the Easy Way tries to achieve.

Can one apply this method to other things? Or rather, what should this be applied to?

Arguably, communication? I am guessing that communication between humans is the most important thing given that human relationships are most important for happiness and there is only action and communication between humans. This would require though a definition of “good communication”, not sure that exists.

What is quality?

When trying to achieve a goal one needs to define it. For example, in private life it could be running: a certain distance in a certain time. In business, it could be the number (#) of user interviews a product manager does per quarter.

These goals often have a unit relating to quantity - the distance in the case of running or the # in the case of interviews the product manager should be doing.

What is the appropriate unit for quality? In the case of running this is simple, it is the speed in which the quantity goal was covered.

In the case of the interview it’s more difficult: is it the number of questions asked by the product manager? The insights (and what is that?) uncovered?

When setting goals for somebody else or a group of people (like in business) the question of defining quality is important since the quantity component otherwise becomes close to meaningless. It’s a big difference if you run 10km in 42 minutes or 65 minutes - 54% lower “quality” if you will.

Solutions to the problem of defining quality in real life:

Break things down to an extreme degree, in sales, for example the number of call attempts

Unpredictable standard set by a powerful persona, a Steve Jobs demanding “better” products

A solution I have not seen but find interesting:

The manager sets the quantity

The employee sets the quality

In case of the product manager doing interviews, if the manager defines the number of interviews, then it is the responsibility of the product manager to deliver what he believes to be the quality possible at that quantity. This is instead of getting into a situation where one side - the manager - demands both more and at higher quality were the employee response with reasons why that is not possible which leads to a tedious interaction. Unless, obviously, the manager is very good and can through basically force of charisma get people to work more and better with the people enjoying it. But, this is very hard to do, so few people can be manager like that.

Software für Sicherheitsdienste / Disponic und andere

Die Sicherheitsbranche wächst mit mehr als 8% pro Jahr. Ein Grund mehr sich der Software zu widmen. Eine kurze Übersicht wesentlicher Merkmale für die Software von Sicherheitsdiensten und wesentlichen Features: Wächterkontrollsystem, Dienstplanung und Abrechnung.

Wachdienste / Sicherheitsdiene - Die Branchen

Sicherheitsdienste sind nicht nur aufgrund ihrer offensichtlich wichtigen Funktionen (man denke an das Oktoberfest und viele ähnliche Volksfeste) von großer Bedeutung, sondern auch als Branchen zunehmend wichtig. Der BDSW fasst regelmäßig Zahlen rund um Ausbildung und Wachstum zusammen - so zeigt sich eine Branchen mit einem jährlichen Wachstum von über 8% liegt der Wirtschaftzweig weit über dem allgemeinen Wirtschaftswachstum. Knapp 300.000 Mitarbeiter und 4.000 Ausbildende tragen dazu bei.

Herausforderungen und Software

Die Branche steht dabei unter erheblichem Druck: gestiegene Anforderungen an Qualifikation und Zuverlässigkeit, Fachkräftemangel und wachsende Erwartungen an Professionalität und Transparenz. Laut dem BDSW nimmt die Aus- und Weiterbildung daher eine zentrale Rolle ein – sowohl zur Qualitätssicherung als auch zur Fachkräftesicherung.

Moderne Softwarelösungen spielen in diesem Kontext eine Schlüsselrolle. Digitale Einsatzplanung, mobile Dokumentation und automatisierte Berichtssysteme entlasten Personal, erhöhen die Effizienz und verbessern die Nachvollziehbarkeit von Einsätzen. Daraus leiten sich auf die wesentlichen Features ab. Wesentliche Software-Anbieter für Sicherheitsdienste

Kernfeatures Sicherheitsdienstsoftware

Die flexible Natur der Aufgaben macht naturgemäß die Dienstplanung (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=D4wMi8Clgc4&feature=youtu.be - ein Video des Software-Anbieters für Sicherheitsdiensteponic.de/). Eine gute Applikation wird aus der Personalplanung direkt Lohn und Faktur erstellen und so die Bürarbeit gering halten.

Offensichtlich ist bei allen Anbieren (beispielsweise auch Excel und mit MS Access selbstentwickelte Lösungen) darauf zu achten das die Forschriften eingehalten werden - beim Wachbuch zum Beispiel die gesetzlichen Anforderungen nach $ 239 IV HGB. Das ist insbesondere dann wichtig, wenn wie in diesem Fall: https://www.disponic.de/modul/wks-und-wachbuch/ das Wachbuch die Dokumentation auf Papier ersetzt.

National Myths

Germans - Nibelungen

England - King Arthur (against the Romans, not only england)

Frankreich - La Chanson de Roland (blows his olifant really hard, enemies bleed, Charlemagne is too late)

Paying with time / Co2 emission comparisons

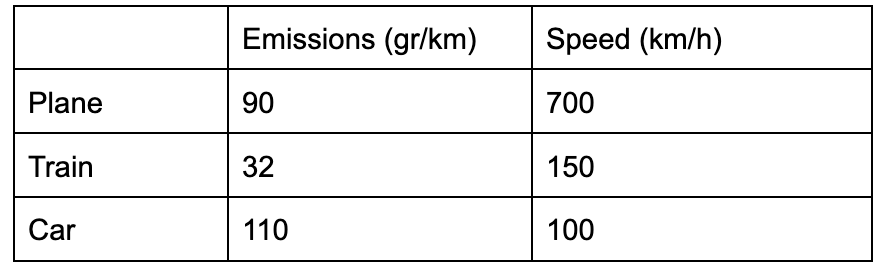

I compared CO2 per distance and time travelled to get a bit of a better sense of the trade-offs.

I first wanted to write about what a protein is, but I don’t get it so I will not. Also I will not finish this article but put it out before I am done.

On a simpler topic: I tend to argue that flying is one of the best uses of carbon that exist. As in, if I had a budget of one ton of carbon, I would probably use as much as possible for flying compared to eating meat, pieces of clothing, etc. This clearly is a personal choice - if one does not need/want to travel then clearly restricting flying to zero makes sense.

Data Co2 Gram per Passenger per KM:

Planes: 90 (Source)

Train: 32 (Source)

Car: 110 (Source)

Obviously there are dramatic simplifications, the car emissions do not take into account the carbon required to build the road and assumes one passenger. The train data is based on the mix of electricity in the grid in Germany 2022 and ignores the investment in the infrastructure. The plane data is used on revenue kilometres, so ignores the shuffling of empty planes.

Next up, speed:

Simply because of the amazing speed of an aircraft and the fact that it does not need rails or roads I’ll keep flying.

For easier maths, that is roughly 4 hours of private flight per month, that is 48 hours per year, let's say 50. The emissions per hour roughly 200 kg. This leads to 10 Tons of Emissions per year.

To offset these emissions, will require a price of carbon. In the EU the ton costs roughly 100€ which is fair - buying those leads to abatement somewhere else. For removal, cheaper options exist (see for example McKinsey) but arguably abatement is better than removal for now which is why reducing the supply in the European market is my preference.

In summary, with 10 ton *100 €/ton = 1000€ a year eliminates the cost of the damage to the climate but delivers 700/150= 4.6 times faster speed than train.

Where the 2/20% Venture Capital Structure Comes from

It is really interesting where the 2/20 structure comes from, as it is in effect one of the most impressives pieces of pricing for a strange type of product.

Again, I just want to get this out there. Venture capital, other private equity and alternative asset classes often get paid in the following way: x% of the total money they are investing plus Y% of the returns they generate above some hurdle. Classic case is 2/20.

There are a many stories where this comes from: whale hunting, spice trading and other stuff. According to a fascinating book I want to recommend More money than God this is not actually true but what dreamed up by the first Hedge Fund guy. This is fascinating to me because the whaling and other stories are told soo often and apparently it is bullshit.

Disqualification - Operationalising the Opportunity Cost of Time

For (Product) it is essential to understand why customers are buying or not buying at what potential product shortcomings are. The problem is that most feedback is meaningless because it does not come from the target customer. The only why to ensure that within the sales process is disqualification.

A couple of years ago, I was at the SaaStr Annual, a software product conference. I started talking to a guy at a stand of a company that sold a software which helps companies handle different currencies. So, their product handle different currencies automatically in case you sold your product for US Dollars but needed to pay you employees in Euro.

After short small talk about how difficult it is to find hotels in San Francisco (where the conference was) the guy asked me a couple of questions:

How many people work in your company?

How much businesses do you do in other currencies?

What was your role in the company?

I was happy to answer because I wanted to get ahead. So many questions how their product worked, what the tricky part of automatised currency exchange trading is, how the payments are handled. Stuff like that which I am just very interested in.

But, I did not get to ask all these questions. Instead, shortly after having asked these questions the guy gave me 5$ Starbucks gift card and thanked me for the interesting conversation. It was very obvious that the conversation was over. So, I walked away, happy about the gift card.

The opportunity cost of time

As a product manager you want to achieve one thing: sell more of your product. There are two ways to do that. One: reach more potential customer who don’t know about your product. Two: understand why customers are not buying and decrease those reasons in order to increase the likelihood of those who know about your product to buy. Side note: please also read these two pieces that matter here: win/loss analysis and product manager metrics.

The problem is that if you start selling a product, there will a large variety of different customers. Those customers will give you very different feedback depending on who they are and what they want. It is however impossible to serve all customers. That is why you need to disqualify customers in order to get the feedback that actually matters. That is also why feedback from your friends is irrelevant unless your target customer is like your friend.

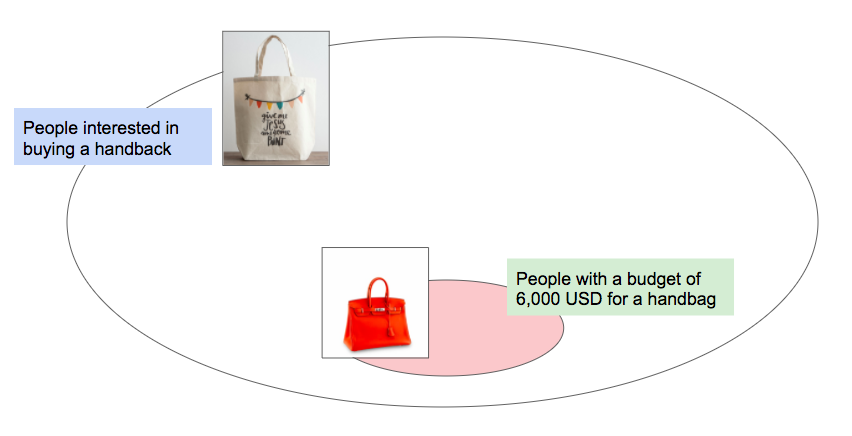

Example: if you are in the business for handbags, you could be selling a Birkin bag or a basic tote bag. Obviously a birkin bag is a different product than a plain tote bag. Just putting a video here because apparently that is how the Birkin bag got famous.

Plus, if you watch the video here your time on my site increases and thats a KPI for me. Anyway, if you look at the simplified market for handbags it looks like the below.

The market for handbags.

If you are selling Birkin bags, you do not care about the largest majority of the market. You are not interested in their feedback and you don’t want them near your store so that they don’t steal the time of those who could be selling to the proper audience. (Yes, I know maybe you actually want some of them in your store so that the people who buy feel special. That is a different point, I am simplifying).

As a product manager you therefore have a very clear incentive to disqualify rigorously. Otherwise any feedback you get has too much noise.

How to qualify

How one qualifies a potential customer obviously drastically depends on the product. For example, if you are a luxury store like Hermes you could put impressive looking people at the entrance. Maybe that will deter (= disqualify) anybody who does not feel the right to enter.

If you have a conversation with a customer you should ask for:

budget: how much are you willing to spend?

need: do you have a gala event coming up where you need a good handbag?

timeline: by when do you need a handbag?

authority: will you be buying this or is your wife the decider?

When there is no a sales team but the product is software driven, a qualified customer might be somebody who has used the product for a certain amount of time or any combination of these features. The goal remains the same: increase the likelihood of a customer to purchase by limiting the set of prospects to the ones that you want.

There is a wide ranging debate on how to qualify a potential customer, in fact, there is even a Wikipedia article on it: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Qualified_prospect.

Disqualification for Product Managers - Conclusion

If your goal is to sell more product you need to understand a) how to win more potential customers and b) how to increase the chance of winning if a customer knows your product.

If you do that for any audience other than your target audience you product is becoming worse because you lose focus. The only way to ensure focus is to have a consistent disqualification of customers who do not fit your product.

Or, build a separate product for those customers - but then disqualify for that product as well.

Market Sizing - A Unit Economics Approach

The size of a market is a crucial input for management decision making. However, most approaches result in large but meaningless numbers. Here I provide a unit economics based approach to market sizing that provides much better insights. Recommended for (product) managers.

I have shared (similar) versions of this articles are also shared on LinkedIn and Medium

Market size estimations often feel arbitrary and pointless

Estimating a “Market Size” used to feel near pointless to me.

How big is the market?

Typically, a "bottom up" and a "top-down analysis" resulted in numbers like “5.2 — 7.4 Billion USD” for whatever the product in question is.

These kind of market size numbers are impossible to manage by, hold accountable for, improve or verify. They are useless numbers.

Market sizing is crucial for decision making

A lot of things are done badly. That’s ok if they are not important. But market sizing is very important. It is the key input for tactical management decisions for example: product investment, marketing goals, sales targets or engineering resource allocation.

GE/McKinsey matrix for market attractiveness

On a strategic level, a lot of management theory concerns the choice of markets. For example “new market disruption” theory points to delivering a product to previously underserved market.

Blue Ocean Strategy argues that creating new markets is the best way of escaping bloody competition in the current markets.

Obviously, both these approaches only make sense if the “new blue ocean market” or the “size of the underserved niche” are geared towards markets that are large enough. In other words — without a good market size estimations both theories are nice but pointless.

Sometimes the “market size” is not discussed openly or not an “official” part of the analysis. Make no mistake — whether the market size is an implicit assumptions or an explicit one it does not matter, it is still the key assumption.

The market size will re-appear at the latest when you fail to generate enough leads in that market or loose deals because there is no demand at a certain price/functionality point.

Market sizing done better: “reverse market sizing” based on unit economics

Core insight:

A market size without an assumption on the price of a product is not a market size. There is no market without price.

Market sizing for product managers - our example

This is the basic concept of what a market is. The price coordinates supply and demand, which leads to transaction (a.k.a. a product is sold) which makes a market.

Example: Component ordering software for independent car repair shops

Let’s say we are considering to build a business-to-business (b2b) software that allows independent car repair shops to compare parts from different suppliers and order them.

The problem this product solves is the time consuming research for the parts and the anxiety of not getting the right price.

Note: I made this up — now idea if this exists or is not possible for any particular reasons.

Now, what's the market size for this product?

Traditionally, the process would look like the below. Much simplified here to make the point.

Bottom-up analysis:

(number of cars in country) * (repairs per car per year) * (average cost of repair per car) * (cost of spare parts) = Big number 1 / bottom up analysis.

Then, you take a percentage of this value and assume that this is your market size.

Top-down analysis:

Find some statistics of the revenue of car repair shops. Make an assumptions on the margin through spare parts. Make an assumption on what you could gather from this. Big number 2 / top down analysis

Is this useful? Yes, this is probably useful to get the very basic statistics. But, it is certainly not meaningful, verifiable or allows us to set useful goals or evaluate the potential.

Reverse market share: ask a better question

A much more insightful way is to put put together basic unit economics of the product we are considering and reverse the market size question.

The question is not “how big is the market?” but “how big does the market for this product need to be to make the economics work?”

A much better question leads to a much more useful answer as we shall see below.

Let’s take the car part example again and do a reverse market sizing. We assume that we would be building a new product. The process would be similar for a new product.

Step 1: investment cost to build the offering for the chosen market

Do a rough and fast back of the envelope calculation of the costs. Components/ services/cost of developer time to build the offering that targets the chosen market.

Step 2: cost per unit of building, maintaining and selling the product

Cost per unit of making, selling and maintaining the product. One can have a detailed accounting based discussion of what falls into which category, e.g. Cost of Goods Sold vs. Overhead. The point here is make numbers you can use, thus I'd go with common sense. Don't overcomplicate.

Making one unit of product:

For example the cost of components and the internal or external engineering time (= cost) required to build it. Of course this depends on the product - in the case of hardware these might be physical components in the case of software components like AWS fees, mail-chimp email service or chat bot tools like intercom or whatever it is you are using. Per product sold - this is unit economics.

Selling the product:

Cost of acquiring a lead, how much time will you need to call or write personalised emails to your potential customers? Will you have a senior sales person with a roller deck of enterprise CIO's? What's the cost per click and the conversion assumption?

Again, this per product sold so you will need to make a number of assumptions.

Maintaining the product:

In case of software there will be an overlap here with the cost of making one unit since typically the components are on subscription. Account for the cost of customer support and other maintenance type costs here.

Step 3: set the price

As we discussed above, you will need to set a price now. Yes, this probably feels uncomfortable. Yes, this is difficult but without a price you are now building a market size. A market without a price does not exist, unless you are building freeware.

If you have no other starting point (competitor research, customer interviews) I’d take a 200% - 500% of your costs per unit sold (step 2). If this sounds high: remember you are pricing the value of your product, not the costs.

Step 4: Calculate your contribution margin

Easy: revenue per unit - cost per unit

A first version for our parts ordering software market sizing effort might look like the below.

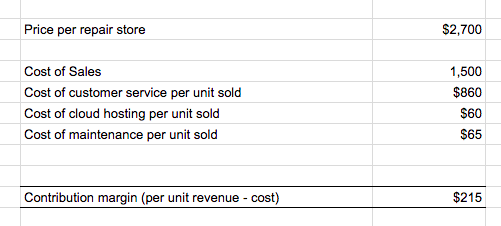

Unit Economics for Market Sizing - Back of the Envelope Example

In our example here the contribution margin is 215$ per unit sold, driven mostly be the Cost of Sales as we see from the numbers.

Since our development cost is 250,000$ we need to sell 250,00/215 = 1,163 units for break even. The math obviously very straightforward.

Compare these results to "The market is between 5.2 - 7.3 Billion USD". From my point of view they are dramatically more useful, because the key elements are clearly identified:

Price

Cost

Break even volume

Now we can verify and work on each element: what can product & marketing do to get the price of the product up? What can What can we do on the engineering side do to get the cost down? How can we reach customer cheaply?

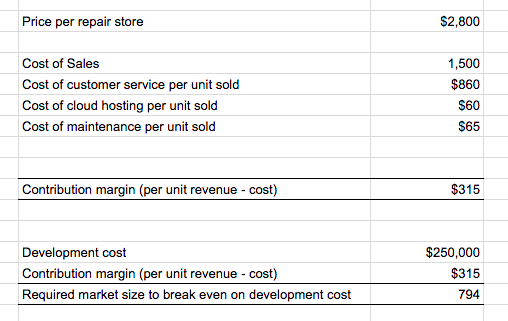

Let's say, we identify that we can increase the price by 3.7% (which I am pretty sure you can always do)?

The effects of a small price increase on the break-even volume are dramatic

In this example, the effects are dramatic - a 3.7% (100$) increase in price leads to reduction of the break-even market size by 31.7% (794 units)!

Price is just one example of the numbers that become manageable. That's it for now, I leave you with a quote:

Unit economics based market sizing leads to real market size and actionable data.

Always interested in feedback, critique and question on the topic. I am at s.buenau@gmail.com