Disqualification - Operationalising the Opportunity Cost of Time

For (Product) it is essential to understand why customers are buying or not buying at what potential product shortcomings are. The problem is that most feedback is meaningless because it does not come from the target customer. The only why to ensure that within the sales process is disqualification.

A couple of years ago, I was at the SaaStr Annual, a software product conference. I started talking to a guy at a stand of a company that sold a software which helps companies handle different currencies. So, their product handle different currencies automatically in case you sold your product for US Dollars but needed to pay you employees in Euro.

After short small talk about how difficult it is to find hotels in San Francisco (where the conference was) the guy asked me a couple of questions:

How many people work in your company?

How much businesses do you do in other currencies?

What was your role in the company?

I was happy to answer because I wanted to get ahead. So many questions how their product worked, what the tricky part of automatised currency exchange trading is, how the payments are handled. Stuff like that which I am just very interested in.

But, I did not get to ask all these questions. Instead, shortly after having asked these questions the guy gave me 5$ Starbucks gift card and thanked me for the interesting conversation. It was very obvious that the conversation was over. So, I walked away, happy about the gift card.

The opportunity cost of time

As a product manager you want to achieve one thing: sell more of your product. There are two ways to do that. One: reach more potential customer who don’t know about your product. Two: understand why customers are not buying and decrease those reasons in order to increase the likelihood of those who know about your product to buy. Side note: please also read these two pieces that matter here: win/loss analysis and product manager metrics.

The problem is that if you start selling a product, there will a large variety of different customers. Those customers will give you very different feedback depending on who they are and what they want. It is however impossible to serve all customers. That is why you need to disqualify customers in order to get the feedback that actually matters. That is also why feedback from your friends is irrelevant unless your target customer is like your friend.

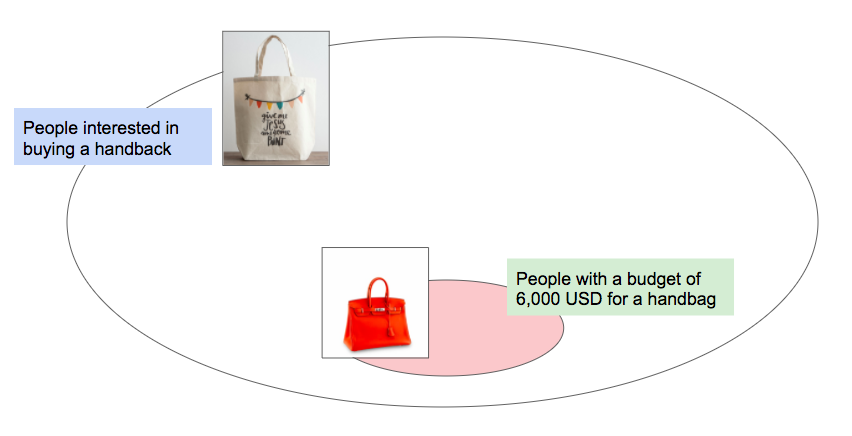

Example: if you are in the business for handbags, you could be selling a Birkin bag or a basic tote bag. Obviously a birkin bag is a different product than a plain tote bag. Just putting a video here because apparently that is how the Birkin bag got famous.

Plus, if you watch the video here your time on my site increases and thats a KPI for me. Anyway, if you look at the simplified market for handbags it looks like the below.

The market for handbags.

If you are selling Birkin bags, you do not care about the largest majority of the market. You are not interested in their feedback and you don’t want them near your store so that they don’t steal the time of those who could be selling to the proper audience. (Yes, I know maybe you actually want some of them in your store so that the people who buy feel special. That is a different point, I am simplifying).

As a product manager you therefore have a very clear incentive to disqualify rigorously. Otherwise any feedback you get has too much noise.

How to qualify

How one qualifies a potential customer obviously drastically depends on the product. For example, if you are a luxury store like Hermes you could put impressive looking people at the entrance. Maybe that will deter (= disqualify) anybody who does not feel the right to enter.

If you have a conversation with a customer you should ask for:

budget: how much are you willing to spend?

need: do you have a gala event coming up where you need a good handbag?

timeline: by when do you need a handbag?

authority: will you be buying this or is your wife the decider?

When there is no a sales team but the product is software driven, a qualified customer might be somebody who has used the product for a certain amount of time or any combination of these features. The goal remains the same: increase the likelihood of a customer to purchase by limiting the set of prospects to the ones that you want.

There is a wide ranging debate on how to qualify a potential customer, in fact, there is even a Wikipedia article on it: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Qualified_prospect.

Disqualification for Product Managers - Conclusion

If your goal is to sell more product you need to understand a) how to win more potential customers and b) how to increase the chance of winning if a customer knows your product.

If you do that for any audience other than your target audience you product is becoming worse because you lose focus. The only way to ensure focus is to have a consistent disqualification of customers who do not fit your product.

Or, build a separate product for those customers - but then disqualify for that product as well.

OKRs for Product Managers

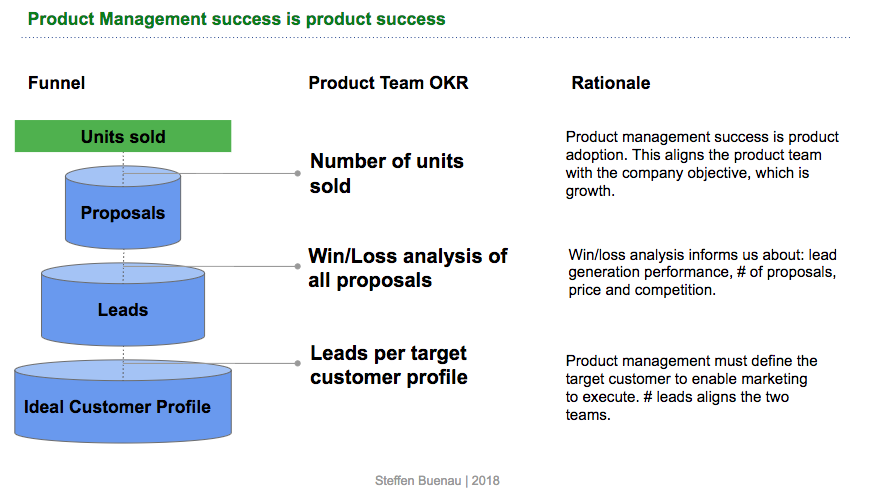

Defining OKRs or Metrics for Product Managers is tricky. Based on the assumption that a product exists and the market is not yet saturated, this piece argues that product management OKRs should follow the funnel. In addition win/loss analysis as an OKR serves as a key business intelligence tool

Defining OKRs or KPIs for Product Management is difficult. Arguably, however good goals are important since product management teams can easily be drawn to the engineering side, the sales side or the marketing side and therefore need clear goals to prioritise actions.

Product Management goals depend on company stage

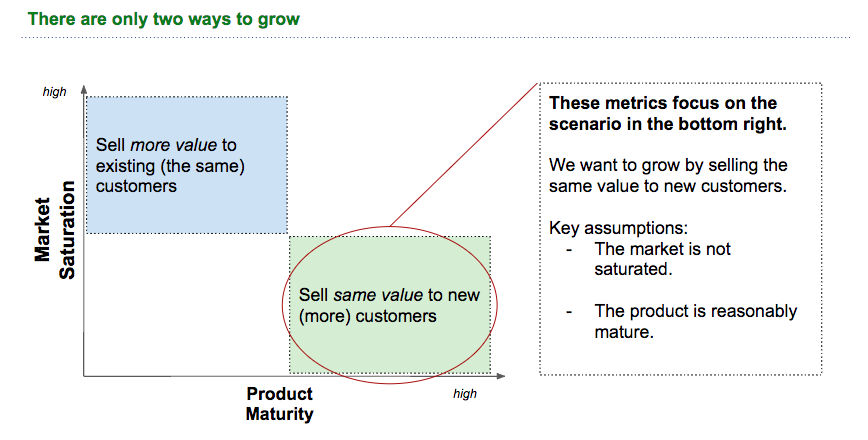

The first step is to clarify where you are in the product life cycle. In the following we assume that the team has a product in the market. In this case there are two options. Case 1: you want to sell more product to existing customers. Case 2: you want to sell the existing product to more customers.

Example: Let's say you are selling a tool to manage your suppliers. you might want to add an additional feature to handle supplier complaint management. If you plan to charge more for this additional feature than this would be case 1. You plan to sell more to existing customers.

An example of case 2 would be that you have so far focussed on selling the tool to car manufacturers in the UK. Now you want to sell the same tool to car manufacturer in Germany. This would be case 2.

The two ways of growth

For the purpose of this article we focus on case 1. The key characteristics are: the product is mature but the market is not saturated. Whether these two assumptions are true will also be indicated in the metrics we are defining.

A good starting point on defining the size of the market is my article on Unit Economics for Market size estimations.

Product success is the indicator of good product management

Product Management teams have the goal to make a company successful by ensuring product success. Product success is unit sold. More precisely it is the contribution margin (= per unit revenue - per unit cost), however here we assume that the product is mature, i.e. a price is set and hence focus on units sold, not revenue.

But, we are not ignoring price - in fact whether we should decrease/increase the price is a key output of the metrics we are about to set.

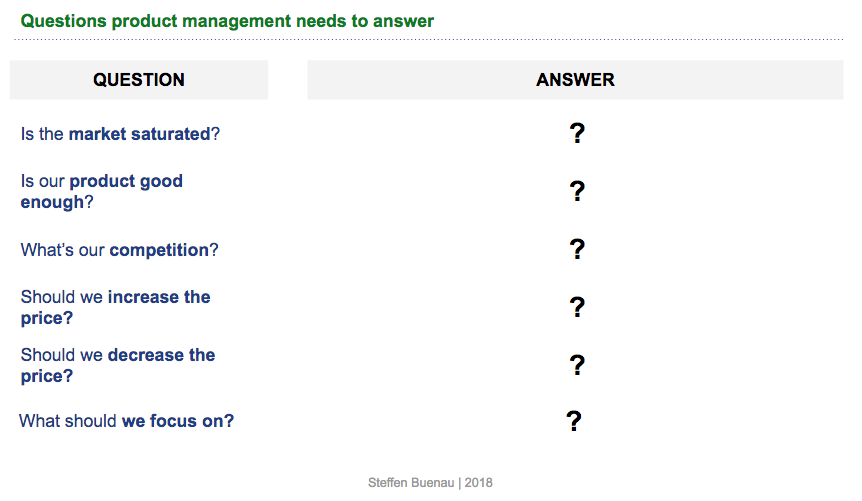

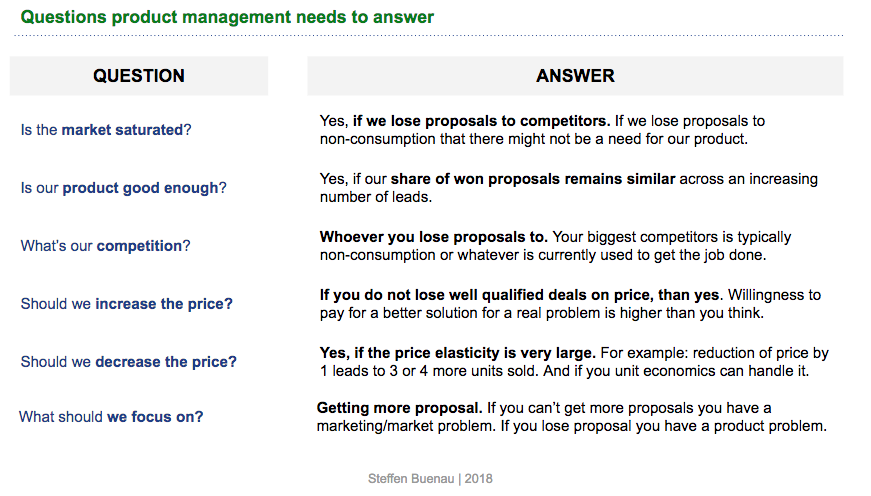

In addition to the pricing element, the OKR system we are designing provides the source for key (company) management questions.

Good OKRs help us define the answer for these questions

OKRs for Product Managers need to follow the funnel

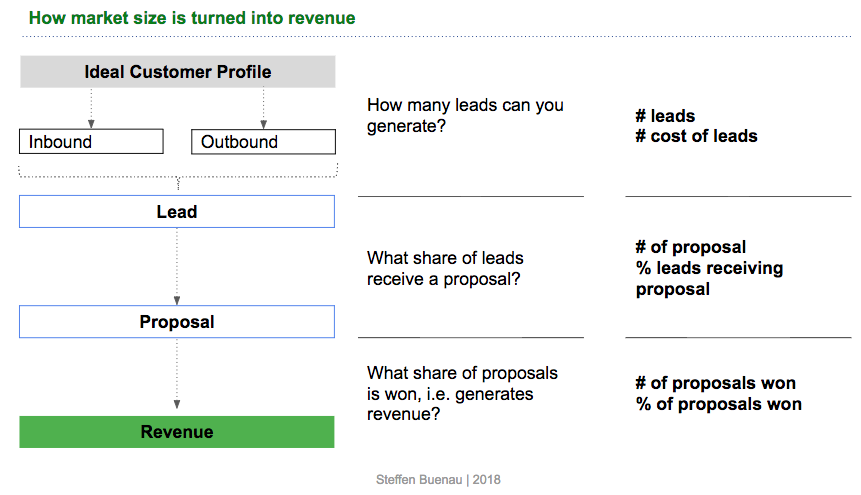

Since we have defined the context and the questions we need to answer we can now design the OKR system.

The rational is simple:

Unit sold (product success) come from proposals to potential customers. Specifically, units sold results from won proposals.

Proposals come from companies or people for whom the product could be relevant. These companies or people we call leads.

Leads are part of the ideal customer profile whom we have targeted either through outbound or inbound marketing activities. Outbound means we approach them first, for example through email or targeted advertisement. Inbound means they come to us, for example through product searches or referrals.

Product Management OKRs along the Sales Funnel

How to use the OKRs

OKRs along the sales funnel align the sales function and the marketing team but go beyond that into product specific insights through the incorporation of win/loss analysis.

The picture is simple:

Lead generation: product management is in charge of defining the target customer, price and features. In the assumed scenario this has already happend. Product teams now need to provide marketing with all that it needs to be able to reach the target customers effectively. These could be classic buyer persona's or things like useful content for the target market or participation in webinars. The problem is that this is not measurable.

Because we are need a measurable metric plus we do not want to measure activity but outcome the most relevant product OKR would be #of leads. Clearly, the execution and messaging is handled by marketing but two align the two teams in the interest of the company #leads is the most forceful tool.

Win/loss analysis: Since we assume a company set up with a Sales Team the conversion from lead to deal is carried by the Sales or the Sales Development Team. In other set-ups like in-app purchase business models these metrics could be carried by a revenue lead. I recommend to listen to the Episode "Revenue is Product Management" by the Mind the Product podcast.

A win/loss analysis will result in three key insights for the product team:

How many proposals do we have? If we do a win/loss analysis on all proposals we will automatically track the number of proposals that we have and understand from which customer profile they come from. This helps the product and the marketing team judge the effectiveness of particular marketing measures.

What share of proposals do we win and why? We care less about won proposals than we think. Generally, we want to know two things: are the won proposals enough to hit our overall volume goal, why did we win them and from which customer profile are they. The reason for winning we want to capture and use as part of our marketing message to the same customer profile.

From a pricing perspective, we want to understand if we could have sold the product to the same customer for a higher price.

What share of proposals do we loose and why? This is the most interesting insight for product management. Did we loose to a competitor or did the lead end up not buying anything for the job our product is meant to get done? If that's the case we might not be solving a problem that matters.

Did the customer not have a budget/means to purchase the good? Than we might need to change our target profile.

Did the customer chose a competitive product? If yes, this could mean the market is saturated or we are not doing a good enough job presenting our unique selling points or product advantages.

Did the customer not buy because of the price? If yes, why and how much lower would the price need to be for this segment of leads to win the proposal.

Beyond the product team - how do our OKRs help the company?

By following this metric or OKR structure we not only guide the product team on what is important: generating more leads that fit the profile, or winning more proposals we also deliver key insights to the management in general.

Based on the data resulting from the OKRs we can help the management answer the questions we posed above:

Sales Channels for Product Managers

This post combines brings together the price of a product, the sales mechanism, the commission for sales staff and the market size to give a holistic way of thinking about the product. Recommended for product managers.

Companies are usually founded to eliminate some type of problem the founders care about. The product the company makes solves that problem and in return for customers pay the company. In other words: a company sells a product.

How exactly the selling happens is extremely important to the company because it shapes the product and the company and consequently if the shareholders of the company are happy. But, it is very rarely explained what criteria to use when choosing a sales channel.

What follows is my best understanding these criteria. The focus is on the mechanisms more than on the exact numbers. As per usual, this is written fast and the result of my mistakes

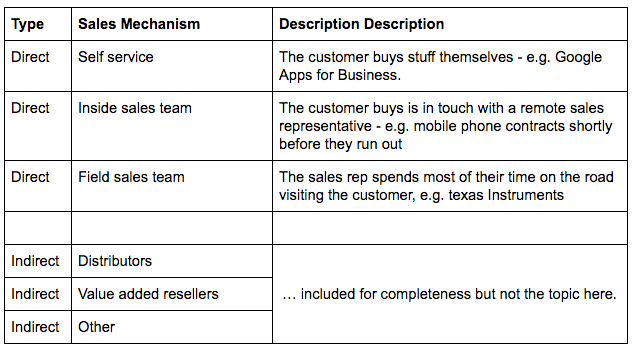

Types of Selling for Product Managers

If you look at sales channels or method, there are a variety of methods. The grouping here is between direct and indirect. Indirect is anything where you are not selling directly to the customer but selling via some other party.

This is an example of self service

Direct sales (where you can engage with the customer directly) are divided into self service, inside sales team and a field sales team.

As an end-customer you deal mostly with self service type of sales environments - i.e. you do not talk to a human before purchasing.

A direct sales approach. Vorwerk vacuum cleaners.

Sometimes you will talk to a human on the phone, for example in the case of insurance or just before your mobile phone contract runs out - this is called inside sales team.

An outside sales team, i.e. people who visit you, are unfortunately not called outside sales teams but field sales team or field reps.

In private life I have only met field sales teams from Jehovahs Witness’ and expansive vacuum cleaners - the picture on the left is in fact from the company presentation of Vorwerk.

Vorwerk calls this "direct sales", I call it "field sales". The world ultimately does not care what you call things but how you understand them, so below you find the summary and description.

Types of Sales

Sales for Product Managers

We will take too approaches to get to the question. First, bottom up: i.e. starting from the cost of a Sales Person. Second, top down, understanding the same question from a company strategy perspective.

Bottom-up: what can you afford?

Before I go further here, I want to admit that I have limited experience selling. I have done both on the phone selling (really badly in my own start up), technical sales support in b2b and field sales but I am in no way an expert and have done each for less than a year.

A salesperson, both inside and field, is compensated through commission. The commission is determined by three things:

a) how many customer interactions do I have

b) what is the likelihood of a closed sales

c) what is the commission for the sales rep at each win

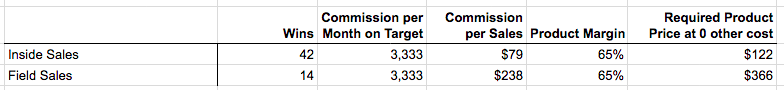

Let’s build the case backwards. Market rate for a high performing sales rep (regardless of inside or field) is 30k Euro fix and with another 40k variable on hitting the sales quota.

The math checks out like this:

How leads convert to commission

Leads: those are simply the amount of people the sales rep engages. For an inside rep I just assumed 30 leads per day and 20 working days. (That means your marketing needs to generate 600 fresh leads per month!). For field sales I assumed 10 leads per day (think about what product Vorwerk is selling).

Win Ratio and Wins: This is just the assumed ration from the interactions. It will depend on your product and qualification but 7% is rather high. Wins is just the the % of the leads.

Commission per Month on Target: as we have discussed before, we need to be able to pay a salesperson 3.3k$ commission per month (40k/12 Months) because that’s the the market rate for this type of labour.

Commission per Sales: this is simply 3.3k$ divided by the number of wins. That gives us how much commission we need to pay per win.

Check and Balances - Unit Economics

So, can we pay commission of 79$ or 238$? Well, this depends on your unit economics.

First, let’s assume we are selling software. Our target gross margin is 65% (See damodaran gross margin tables). That means producing and selling the product is <35% of the price.

If we set the cost of making the product and generating to 0 than the minimum price is: (commission) * (1/0.65). Obviously, that is a crazy assumption because we are not not spending any money on lead generation which will be key to maintain your sales team. Plus there is no budget for running the product, for example AWS fees, etc. This is a crazy assumption used to make the point.

Margin and product price

The answer:

In short, given the above assumptions if you product is below 122$ then inside reps make no sense. If you product is below 366$ then field sales makes no sense.

Cour product margin or conversion rates need to be higher or your sales people need to be cheaper to make it a good business.

But Customer Lifetime?

The lazy way out of this debate is to argue - once I have a customer, he will stay until infinity (e.g. in case of Netflix) or he will buy more stuff from me. That is a lazy argument and not valid until proven otherwise.

Top-Down Sales Strategies for Product Managers

This part begins with the interest of the shareholders. If you own the company yourself than obviously you can do whatever you want. But, let’s assume you are venture capital backed and need to grow a unicorn.

The product is still software, so we know the enterprise revenue to sale multiple. It is about 7 times revenue. To be a billion dollar company we need to do about 1 billion / 7 = 150m $ revenue.

The math looks like this:

Market Size for Product Managers

Let’s assume you can do 10% market share. Whatever you are selling, is the market size at 50$ for your product 30m customers? Be critical about this, even when you are selling something that costs 500k per year you will need 300 customers to achieve the returns you promise to achieve.

The rest of the math stays the same. Pay market rate and control for unit economics margin.

Conclusion:

Why are mobile phone contract sold with inside sales reps? Because the cost of a mobile phone contract is essentially 0 - except for the cost of the sales person. A 2 year contract at about 50$ a month is worth 1,200$ and the likelihood of buying is high because everybody needs one.

Also: make conscious decisions about your price and sales mechanism.

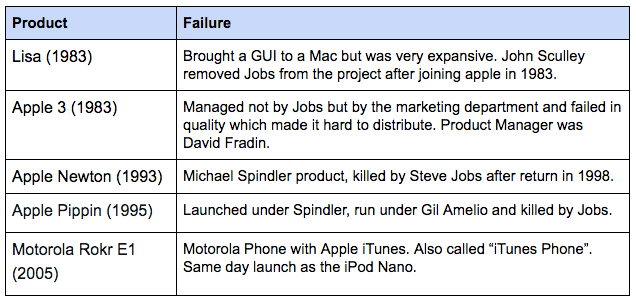

Failed Apple Products

Another article written for myself. Failed products from Apple, the most interesting ones and who managed them.

his post accomplishes two things for me. First of all, I have to get my facts straight and remember them. Second, I have (anecdotal) evidence for what I believe in terms of product development.

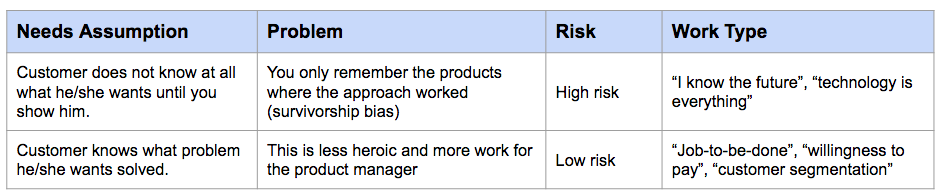

I believe there are two roughly approaches of buildings products. One, is the visionary technology approach captured in quotes like “people don't know what they want until you show it to them.” (Steve Jobs). The alternative process is a jobs-to-be-done approach, that assumes that you can identify at least the problems that need to be solved and approach.

Summed up, you could look at the differences like this. This is extremely rough and definitely not mutually exclusive/commonly exhaustive.

Definitely an incomplete matrix

The outcomes of the first approach can be very impressive, i.e. the iPhone. The problem is that if you only see the outcome and ignore the failures (= survivorship bias) it looks like that’s the only way to build. That is risky because in order to get to an iPhone-like product you need to have the stamina and cash to survive the failed product which you don’t see when you just look at the iPhone for example.

That is why I am listing some of the biggest failed Apple products here, to remind myself and those who read this. In any case, the iPod, the iPhone and the MacBook air are amazing products.

Incomplete list

The selection is not complete but based on what I find interesting.

On apple and this issue I recommend these resources:

- https://blog.aha.io/why-i-failed-with-the-apple-iii-and-steve-jobs-succeeded-with-the-macintosh/

- https://shows.howstuffworks.com/techstuff/how-apple-survived-the-pc-wars-part-one.htm

- https://shows.howstuffworks.com/techstuff/how-apple-survived-the-pc-wars-part-two.htm#

- https://www.forbes.com/sites/chunkamui/2011/10/17/five-dangerous-lessons-to-learn-from-steve-jobs/#32e10fa03a95