What is a company? A Product Management Perspective

Since I haven't studied business, my business knowledge is pieced together. For things like cost of capital, public and private equity, tradable vs. non-tradable debt or "alpha" the basic mechanics plus why they exist make sense. (Also the beauty and creativity of the concept of a legally limited entity is clear - e.g check out this piece)

But, it took me a long time to understand the relationship between product and company - from an operating business perspective. Not, for say a holding company.

An operating company generates revenue from the selling of products. That is why a product is the starting point and the unit of analysis to get to the core of it.

What is a product? Whatever has a price.

We define a product as what brings revenue to the company. For example, the product of Facebook is a click on an add. The product of a bank is the fee or interested charged on a loan.

A feature - in contrast to a product - does not have a price but is a characteristic of the product. For example, "groups" in Facebook might bring more people to Facebook or make them spend more time on Facebook which increases the odds of people clicking on a link. But, the number of groups on Facebook is irrelevant for it is not directly tied to the price per click Facebook charges it's advertisers.

A feature of a loan might be that repayment starts only after 5 years. If for example the loan is targeted at people starting a 5 year doctorate program. So that repayment start date is a feature, but does not directly change the revenue. (Yes, I understand time value of money but that is accounted for in the interest rate).

Another way of formulating what a product is, is (number of product) * (price) = revenue from that product. The product is whatever has a price and therefore generates revenue.

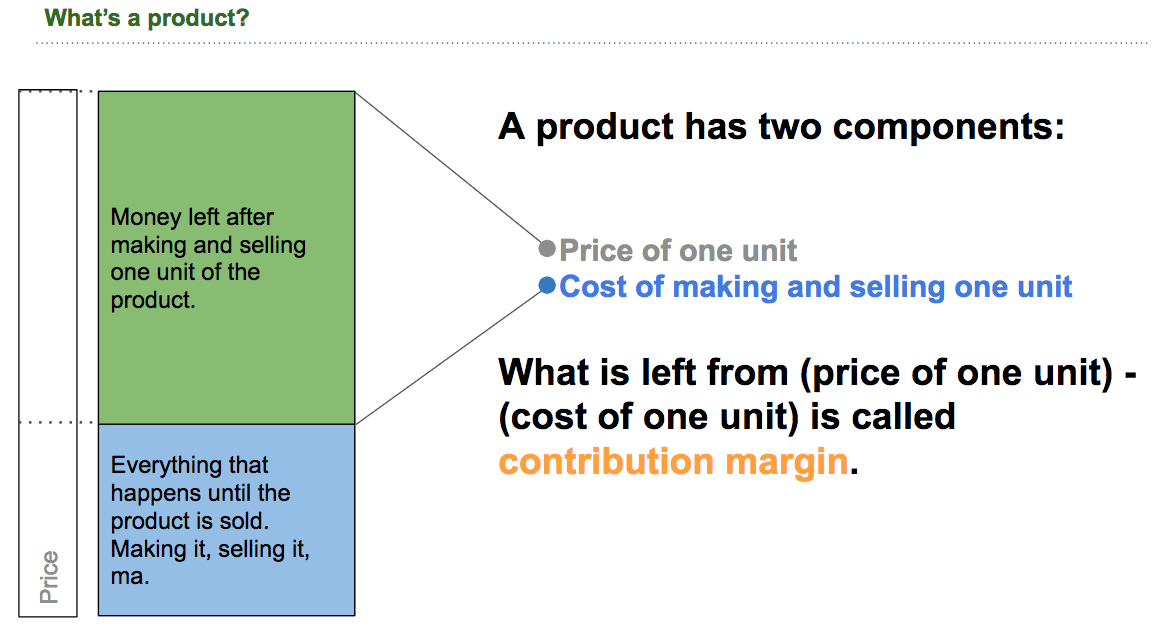

The two features of a product

Basic product costs...

Now, since the unit of analysis is the product we split costs between "costs per unit of product" and "overhead".

This obviously depends on what you are selling and how you sell it. For example, if you are McKinsey & Co. your product is a consulting contract. The costs are the salary of the people making the analysis and travel expenses. The cost of sales is maybe the membership of a partner in a high level working group, the golf club membership, travel and hosting expenses.

If you make iPhones, than the product is one phone. The costs are the components to make (< 400$ check out this analysis), and other cost associated with production and sales and marketing.

In our example above, if you are Facebook, the major cost is having the users that click on the advertisement (which is the product because it has the price money).

From an accounting perspective, this is akin to the variable costs. The logic of the variable costs is that they increase with additional output. So, if you build a car, than you got to buy 4 tires for every car. So the more cars you sell the more tires you need.

... and more tricky product costs

The accounting perspective on product cost is much more straightforward than it is in reality.

Say, you offer the customisation of a hardware product at a low price. The customisation price either exceeds the labour costs of doing it - than it is its own product.

If it does not than it is either "overhead" or "unit costs".

But which one - this depends on two questions: "Would you sell less units if this feature was not offered?" - if yes, than it is product costs and part of customer acquisition costs. If not, than it is overhead. If it is overhead, than this is part of company strategy either implicitly or explicitly.

A similar case are support and service teams - from experience we can see that the "does it increase units sold?" test often determines service quality. Either:

it has price, than it is a product

it increases volume sold - than it is part of customer acquisition costs

it is neither, than it is overhead

Products that operate in a low competition world - Internet, mobile phone, telephone - have low customer support/services. This is because having it will not drive units sold or would be an extremely expensive way of doing it. You need an internet connection. Once you have it you are in a long term contract so spending money on support is pointless.

The alternative is true for a company like Zappos. Retail depends heavily on customers buying repeatedly. Hence, every support interaction can be associated with volume increase, so it is a cost that drives volume sold and therefore accounted to the product in the customer acquisition cost bucket. A metric to use could be: "share of customers that order in 6 months after a support request" - compare this to the general re-order rate and you have a first meaningful piece of data.

Contribution margin

The difference between the price of a product and the cost of that product is the contribution margin. Revenue per unit of product - Cost per unit of product

What is a company? The sum of its products

In this framework of analysis, a company is simply a collection of the products that it sells. For a company to exist, it either needs to be profitable or get funds by taking loans or selling parts of itself (= investors on board). In the short and medium term investors might sometimes care more about revenue or user growth than they care about profits - but in the long run profitability is king, because cash is.

That means, all the costs of a company that are not part of the product costs must be carried by the contribution that each product makes.

In other words: you have to pay everything that is not directly linked to a product from the contribution you get from other products.

The amount of money available simply is the contribution margin multiplied by the number of times you sell that product.

Given this scenario, two things become apparent. The goal of the overall management (on the left) and the goal of a product manager.

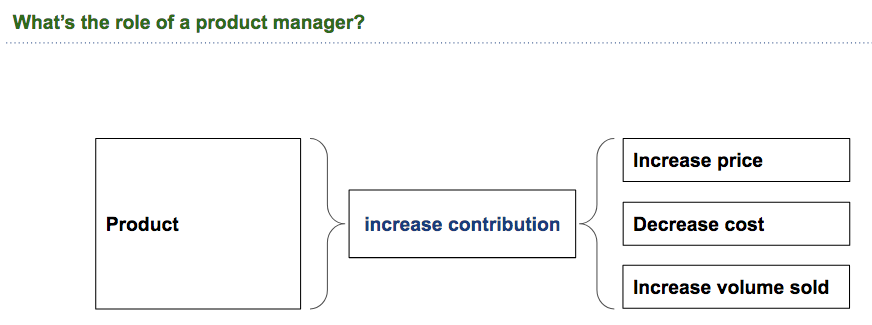

Product management: Increase the contribution

Given this approach to a company, the role of a product manager becomes relatively straight forward as well.

Essentially, increase the contribution of the product to the company. There are just three tools to do that:

increase the price,

decrease the costs

increase the volume sold.

Product Management is increasing the contribution of the product to the company

(Besides discussions about launching a new product. Separate piece coming on that.)

In this light, a typical discussion, for example, if a certain feature is worth it can be discussed in a useful framework: Will it increase the volume? If so how?

By reducing lost deals? (how many do you loose right now because you don't have the feature?)

By bringing in new potential customers? (does marketing know?)

Hope this is useful!